PERFORMING the STRUGGLE || chapter two || three letters and some postcards

Many migrant workers in north-western Europe come from former colonial territories – West Indians, Pakistanis and Indians in Britain, Algerians in France, workers from Surinam in Holland, etc. Their working and living conditions are often similar to those of migrants who come from southern Europe. They experience the same exploitation. But the history of their presence in the metropolitan centers belongs to the history of colonialism and neo-colonialism.

John Berger, A Seventh Man (1975)

Away from Home in Lecce

Chrisina Thomopoulos, artist and activist (Athens)

I arrived at Free Home University’s (FHU) two-week winter residency full of questions about myself and those around me. Who are we? What is most important, necessary, and urgent to us in this moment? What is missing? What are the daily obstacles some of us are forced to face, in this time of artificial borders? What might a group coming from different parts of the world achieve together in fourteen days?

(Or, in thinking with Cornell West: What does integrity do in the face of oppression? How does honesty face dishonesty? How does virtue face brutality? How does decency deal with insult?)

We were invited to explore the idea of “performing the struggle,” thinking and acting on radical pedagogies. Around fifteen strangers and near-strangers meeting, learning from each other through an intense yet temporary everyday life together, trying to build bridges in a time of walls, fear, suspects, separation, bans, and hyper-mediated hate. We are still reflecting on what we achieved.

Free Home University is where A, L, Am and I met, in Lecce, Italy. All of us were far from home, each of us in different ways: some forced to leave, some with the option of movement. Perhaps being in another place, “away from home”, gives us a way to speak and listen, to risk, to try things out; unconsidered approaches, grounding discussions in context, attempts for actions. In between our dense performative workshops, we also cooked and ate together, and spent time just talking and hanging out. During some of our lunches we shared texts that have been influential for us. During one lunch I presented the work of visAvis: voices on asylum and migration together with John Berger’s A Seventh Man, trying to connect past and present documents on migration.

At the end of our two weeks together, when it was almost time to say goodbye—after all we had shared and learnt, after our public performance and final party, after our last home cooked dinner—I asked A, Am and L: Is there anything urgent you would like to share with the world? Something you would like to write, that is important for you to communicate right now? These questions led to a conversation in which A, Am and L shared their stories with us, and agreed they could be transcribed to contribute to visAvis and others publications.

Besides a light line editing for the English translation, the stories are kept as they were told, in the colloquial and intimate style they were offered, as personal narratives of these young men who lived the experience of crossing the borders and being displaced, still seeking refuge in Europe, resisting hostility and exercising resiliency.

Letter 1:“We can not take you to the doctor”

A.B., asylum seeker participating in Free Home University

I arrived in Lampedusa, Italy, by boat on August 4th, 2014. After my arrival, I was transferred by bus to Vicenza. I stayed there for two months. After that, the prefecture transferred me to a small village, Sandrigo, close to Vicenza. I lived in Sandrigo for six months, and then I was transferred back to Vicenza. I have been volunteering in the municipality of Vicenza, and I got a three-month contract to paint the benches of the children’s recreation ground. At the end of these three months, the assignment finished, and after a few days, I started suffering from a serious headache. I suffered a lot for three months, so badly that I was not able to work, but I did not see a doctor. I told the NGO that was in charge and had supported me, that when I had this headache I was not able to see anything. They replied: “Since you have been in Italy only for one year, we cannot take you to the doctor. You have to go to the doctor alone.”

Then I went to the ER where I was told I had to do medical examinations. But my health insurance had expired, and I was not allowed to get any medical assistance without that. I asked the doctor who visited me “What did you see? What is the problem?” He said to me, “There are two scars in your eyes, which are like two hands in front of your eyes.” I went back home and I asked the NGO to renew my health insurance, but in order to do that I had to get a new residence permit. I had to wait for four months to get my new residence permit. So, all in all, I spent six months staying at home waiting for the documents. I was not able to go to school or do anything else. Just waiting.

When I finally got my residence permit, I received the medical examinations, and asked if I could have eye surgery. They replied that the scars could not be operated. I continued taking medicines. I had to do the Italian language exam, level A2, but I was not able to do that because of the pain in my eyes and head. Finally, the doctors told the truth to the NGO: there are no solutions and no medicine for my eyes. There is only medicine to reduce my headache. When I heard that, I said “I’d rather die than live with this problem.” So they tried to help and encourage me, sharing examples of people who live with this problem, even more serious than mine. The NGO helped me face the problem, provided the eye drops and glasses. I have to wear them all the time. The situation has improved, and now I am better. I can read and write.

Two months ago, I arrived in Lecce, and I have enrolled in an Italian language course, level A2C. I am studying and preparing for the exam.

Letter 2: From Libya to Italy: fleeing from lesser problems to greater ones

A.E., asylum seeker participating in Free Home University

What is really going on in Libya’s prisons? I don’t really know if the IOM (International Organization for Migration) or the WHO (World Health Organization) are ignorant or not, of what is really going on in Libya’s prisons.

I was imprisoned in Libya for more than two months in five different prisons.

While I was in these prisons, the WHO paid visits. The Libyan police would not allow those of us who would speak up about what was really going on in the prisons to do so. Rather, the police officers would select people to speak and say only that which would benefit them [the police]. One day we were expecting the visits of the IOM and the WHO. We grew hopeful that this would impact our condition. The authorities cleaned the entire prison, the bathrooms, the surroundings; they maintained the whole place as if that was what it usually looked like. But the place was not for human beings. It was more like a place where animals live. They clean for these visits to hide this.

The police threatened the people who would speak, making it clear that if they say anything bad, they will be killed as soon as the interview is over and the officials have left. The police will kill anyone who criticizes them. For this reason, I feel the IOM and WHO are ignorant of what is going on.

But in another way, I feel that the WHO and the IOM are not ignorant of what is going on. They see people in prison with many bruises and injuries. Many are half-dead. And they witness this with their own eyes. They cannot be ignorant of what is going on.

All the organizations and the police want deportations. The police gets more money if they deport people. That is why most of the police in Libya arrest people left and right. Every day they count the prisoners. They tell us “Today we deport Nigerians, tomorrow people from Gambia”; and they are arresting more people in the streets.

When you try to ask the new people what happened to them, you hear the same story: they were coming back from work and the police picked them up and took them to prison, without them doing anything wrong. Same story every day. It even happens that the police go to some houses, find out that there are black people living there, and throw them in prison for no reason. Libya is not safe for people to live in. And I feel the UN is aware of all this.

Even when people ask to be deported, the Libyan authorities refuse to take them back to their countries. They will tell them they are deporting them, but then they just transfer them to another prison. I have been a witness of it. I was transferred from Sara Dine prison to White House prison, from White House prison to Underground prison, which was holding almost 1000 prisoners. They have not seen the sun for more than one year now.

Much pain here. It’s not easy to remember all this. In the prison, two people I knew died. They gave up. I was talking to them every day.

People are dying silently in Libya’s prisons due to the lack of European awareness. People are being taken from one prison to another, exposed to torture everywhere. People are dying in Libya, and Europe is ignoring this situation. Can we continue to live like this? The European governments should respect human rights and come with resolutions or put pressure on Libya, instead of allowing people to die in Libya’s prisons.

It is with a deep sadness that I acknowledge that I maybe lucky not to be among those that are dead now. But people are there. Deeply in pain. And they feel abandoned by the people in power, by whom they hoped to be saved from what they are going through.

There are more stories about things that are going on in Libya. I hope to be able to write more of them.

It took us twelve hours to cross the Mediterranean Sea in order to come here, to Italy. I didn’t know what was going to happen…

I believe Italy may be the worst place. The way we are treated… They stop us on the street… Even if you speak Italian, they won’t listen to you. The way authorities treat us in the camp in Bari was not encouraging. We try to tell them about our problems, and it only gives us bigger problems. Our rights are not respected. In the Bari camp, the toilets and the showers were so bad that not even a dog could have used it. And when people try to speak their mind, they tell us, “You were not forced to come here,” so we don’t really know what to do.

When entering a bus, the driver has the right to ask for your biglietto (ticket). But they ask because you are Black, while I noticed that they don’t ask the white person. I feel they assume you don’t have the biglietto. And in some cases, even when you show the ticket, they will ask for your documents. And if you fail to show them, they ask you to get out of the bus. The bus drivers are not allowed to do this, only the police and the border officers can check the residency documents or your status. We are tired of these things happening in Italy. It’s not only me. The majority of migrants experience this situation.

There are many difficulties and a lot of pain. It has not been easy. Sometimes I don’t know if it’s better here in Italy or in my home, in Nigeria. I really don’t know. In Nigeria senators received almost 2.03 million (Nigerian naira) as a salary every month. The deputy president receives 2.31 million and the president of Senate receives 2.48 million. This is a monthly salary for just one person! There are good resources there, in terms of oil, but because of corruption the refineries are not working, they export oil to other countries, and the oil is then imported back to Nigeria, all because of corruption and embezzlement.

In Nigeria I see that a single person has enough money to feed the whole country. So we have everything. The problem is that those in power control everything. To whom can I say this to? Who will listen? Who will solve the problems?

Only two times have I felt happy during this year I have spent in Italy.

The first time was with Silvio when we did a shadow theater workshop. The second was yesterday evening’s performance at the end of Free Home University’s session. It was really wonderful and beautiful and I felt like a new-born baby. Everyone there were the best people I have ever met in my life. They were all open and willing to understand. They were sharing our pain and thanks to their understanding, I felt that there is always life, that all hope is not lost. That we should keep on fighting. Because when there is life, there is always hope.

Letter 3: We all have a story to tell, here is mine.

Liltrez@brocus, asylum seeker participating in Free Home University

Sometimes we have to let the world know about ourselves. Life is not a film. That’s why we have to be careful, because a time will come when someone will ask us about our story. That one is our Father, the Lord. And when that time comes, I want to be in a good position to be among the chosen ones.

My name is A. L. J., which means eyes of the world. I was born in 1991 and I am from Nigeria, Edo State, but I am now based in Italy. I am an artist; I love singing, dancing, and making videos. Once I was a director of a theatre, DFM entertainment, and I have also been the director of Uwhosendan Entertainment. I lived in Nigeria for 21 years, and during that period, I was not educated because my parents were very poor. My mum gave birth to 11 children, and I am the seventh one. I could not just stay uneducated, so I searched for a job and later I became a warder and I worked for four years. On March 11th, 2011, at 11:00 am, the gas exploded in my eyes in the store where I was working and I was rushed to Nigeria hospital UBTH for treatment. Since I had no money when I got there, the doctor did not attend to me immediately. My eyes got worse; they became like cooked eggs. I couldn’t see at all. Later, my family finally found some money and I started the treatment. I had two operations in both eyes, but they weren’t getting better. I spent two months in the hospital and the doctors told me there was nothing they could do. I was discharged because there were no solutions. I went searching for treatment in other states and other villages, but there was no solution. I lost all my friends with whom I used to make music and entertainment. I also lost my girlfriend. She left me too, because she could not date a blind person. Even people who did not know me before did not like to come closer to me.

Sometimes when I was walking in the street, I would fall into a hole and hit myself on something. I had a new girlfriend. Her name was Rejoice Ina Jimmy. She helped me a lot and she always told me that I would see again, but my mom didn’t like her because she was not from my state, Edo State. My mom believes that people from other states are not trustworthy. Her father had told her bad stories about people from Ondon State, but I loved her so much and she was everything to me, to cut the story short.

Things were really difficult for me in 2014. Finally, I decided to go far away to another place, where even if people would hate me, they would not know who I was, or my background related to the eyes.

I left Nigeria on July 27th, 2014. I went to Kano, from Kano to Niger, from Niger to Saba, and from Saba to Libya. It was very difficult because I didn’t even know where I was going. Sometimes I felt like killing myself, but death does not come easily. I always knew inside of me, though, that it would not be like that forever, and I was dreaming about waking up and seeing clearly with my own two eyes. In my dreams, I sometimes saw myself on a big stage, singing and dancing, with people applauding my performance. Then, after having spent a long time in Saba, I went to Tripoli where I met other friends who were taking care of me. Sometimes when the “Asma boys” (gangs of young armed robbers) approached me and my friends to steal money from us, my friends ran away and I was left alone because I could not see and I did not know where to run. Since I did not have enough money they would beat me and go. Due to all that, my eyes got worse, until a day I met a man who came to pick me up in the night and took me to a place where I met other people. There was a huge sea there, called the Mediterranean. They took me inside a boat sailing to an island called Lampedusa. There were so many people on the boat. For eleven hours, we sailed through the night. The next voices I heard were people grieving, complaining, shouting, but also languages I didn’t understand. Later I found out that Italian rescuers approached us.

I heard their voice “You are welcome to come to Italy.”

They helped us and brought us to Sicily. So I was in Sicily, Italy,as a refugee. From Sicily, I was transferred to Brindisi (Apulia), where I spent three weeks in the Green Garden Hotel. Then I was transferred to Lecce, where I live now. I was in a project called SPRAR[1] run by the NGO GUS. They helped me with my documents, the residence process, and everything else, and they took me to the hospital in Lecce. There, they told me that they could not do anything about my eyes because they didn’t have the right machine to examine the inside of the eyes. So they referred me to Bari, the only hospital that has such a machine. We went there on the 9th of November for a medical examination, and the doctor said they would be able to do an eye transplant. After the operation, it would take two to three months before I would be able to see again. They would do one eye first, and then after a long time the other. They booked an appointment for me on December 19th, but I believed God helped me to have it before and I was called for a cornea transplant on December 15th. So that day, at 11:35 a.m., I was brought to the hospital. The last thing I remember was having the drip fixed and smiling because this operation would have made me see again.

All the time I had spent in Italy and I didn’t even know what it looked like.

I woke up after the operation. It was night. I didn’t know what time it was because no one was there to tell me and my eyes were bandaged. Later a nurse came in and called the doctor. They removed my plaster and I couldn’t open my eyes. They tried to force them open a little, gave me eye drops, and shut my eyes again. In the morning, they came back again and removed the plaster: I could see like other human beings, as clear as I had never imagined after five years of blindness!!! It was strange, and the doctor was shocked because they had never expected that I would be able to see so clear so soon. Everyone was happy, including me, and I came back to Lecce.

Meanwhile, I was introduced to the project Free Home University in Ammirato Culture House. There I met new people who have made me alive again and who became close to me: Claudia, Silvio, Alessandra, Federica, Nicoletta, Alessia, GianAndrea, Gianluca, Broslolo, Rolando, Mama John, and Aghedo with whom I made video clips, images, theatre, and many other activities. It was really fun, and cooking was going on as well.

On December 9th I went to submit my request to the Official Commission to be taken care of by the Italian government as a refugee. Now I can see again, and at least I have documents (residence and health insurance).

So that is my story, but I have to say a big thanks to those who were really helpful to me. The first one is the Creator. I thank you Lord, for all you have done in my life. You removed the garment of shame from my life and you made me see again, and you made me useful to the world. You will always be in my memories. I can’t reward you enough because I don’t have what it takes, but one thing I can do to pay you back is to always have a pure heart and help those in need and tell them about you so they can find comfort in your house. I feel love for you, deeply in my heart. I can’t wait to see you. I am expecting that anytime, because I can’t wait to be with you. I love you a lot. Forgive and have mercy upon me and put my name in the book of life. I know I am not alone, that you are always with me and make me believe. Thank you a lot! You are the best!

I thank my father and my mother, I thank you both for bringing me into this world and, I thank you, mom, very much for all the pains, all the tears I have caused you, for the gift of having being carried for nine months in your womb. I love you mom! You are the best! And I will never forget you. You will always be in my memories. I like you, dad, for providing all that it takes to bring me hope and for being a father to me. I am proud of you, dad, and I miss you! You will always be in my memories. God will never let something happen to you and mom. He is always with both of you and I wish you a happy married life as I understand you both are the best lovers. I miss you and I love you both, deeply from my heart.

And to your other son, my brother Amadin Broslolo, I say thank you very much for all you have done for me. You make me alive, you give me everlasting life and make me believe that blood is thicker than water. Don’t have much to say, only God will reward you. I love BigBro!

Thanks to my family: Mama Blesing, Mama John, Bros Festus, Bros Omo, Mama, Lolo, Liltrez, Silvia, Roland, Odan, Ovaka. Special thanks to all of my friends that I love so much and to the pastors.

Don’t forget we all have stories to tell. I believe in myself, like in the air that I breathe and that is in me.

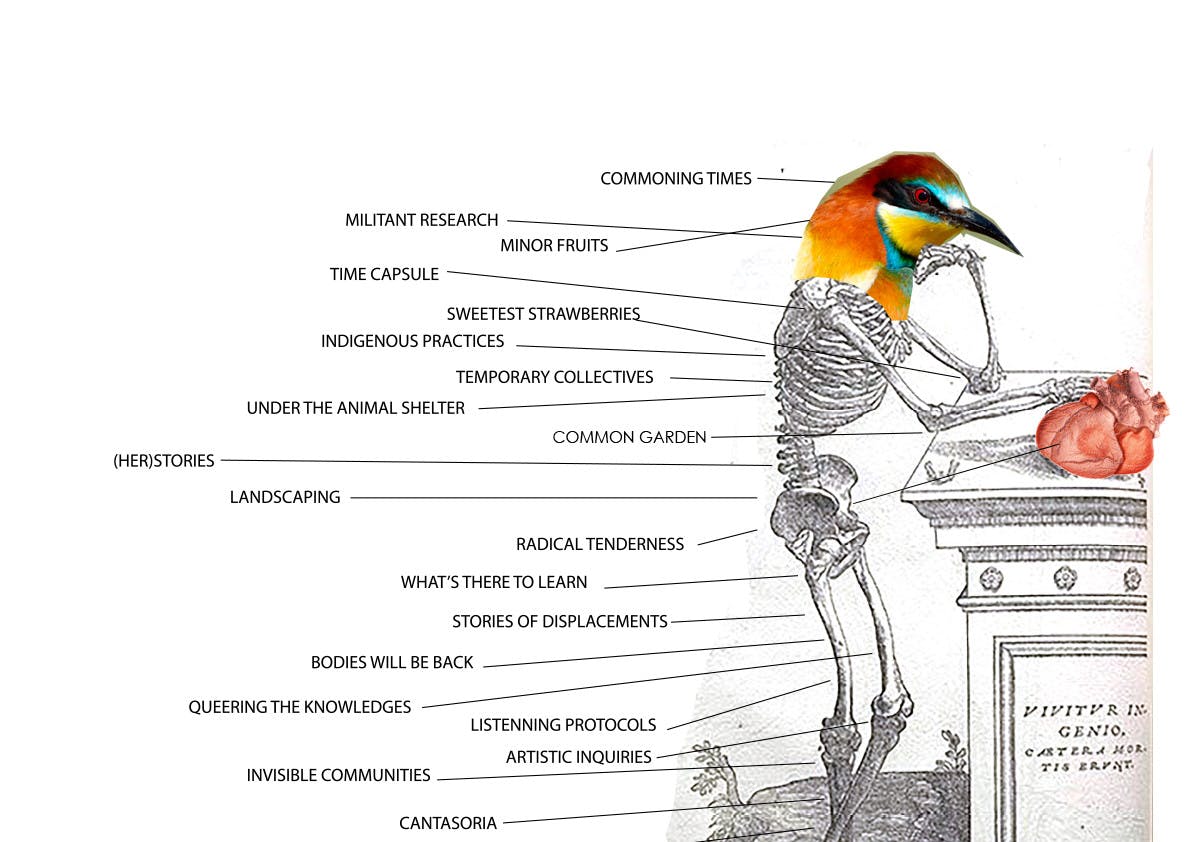

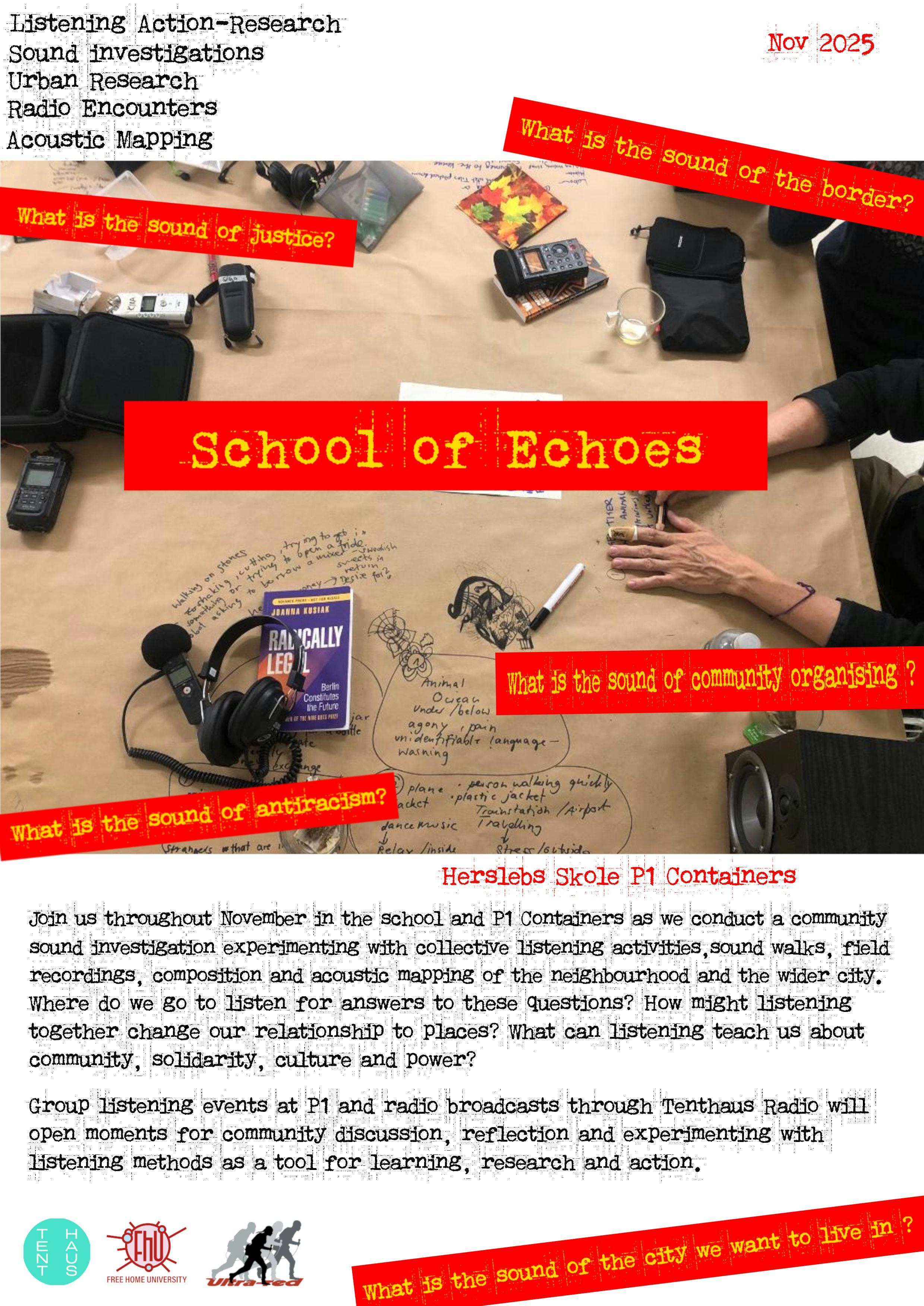

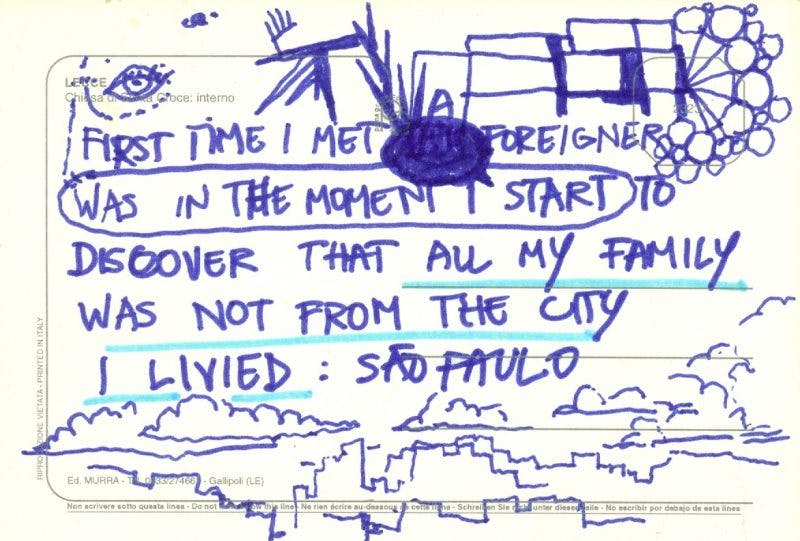

Foreign Postcards: A Series of Rituals around Language, Memory, and Music

When was the first time you remember hearing the word “foreigner”? What happened?

From whom did you first hear this word?

How did you feel upon first hearing it?

These are some of the questions I started posing to myself as part of my personal search to understand what it means to be a foreigner today. My search began in 2011, at a moment when I found myself in transition, trying to piece together the roots of my own experience of foreignness and diaspora. This search gradually turned into a shared process with friends and strangers, sometimes through experimental workshops and other times via spontaneous discussions.

In Lecce, another episode of this discussion took place in various spaces of Ammirato Culture House over the course of our two week session of Free Home University in the winter of 2016.

Woven throughout these stories are some of the postcards written by those who gathered through this exploration in Lecce.