The Fate of an Insect... || essay by Silvia Maglioni & Graeme Thomson

The Fate of an Insect that Struggles Between Life and Death Somewhere in a Nook Sheltered from Humanity is as Important as the Fate and the Future of the Revolution [1]*

a conversation between Silvia Maglioni & Graeme Thomson around People of flour, salt and water

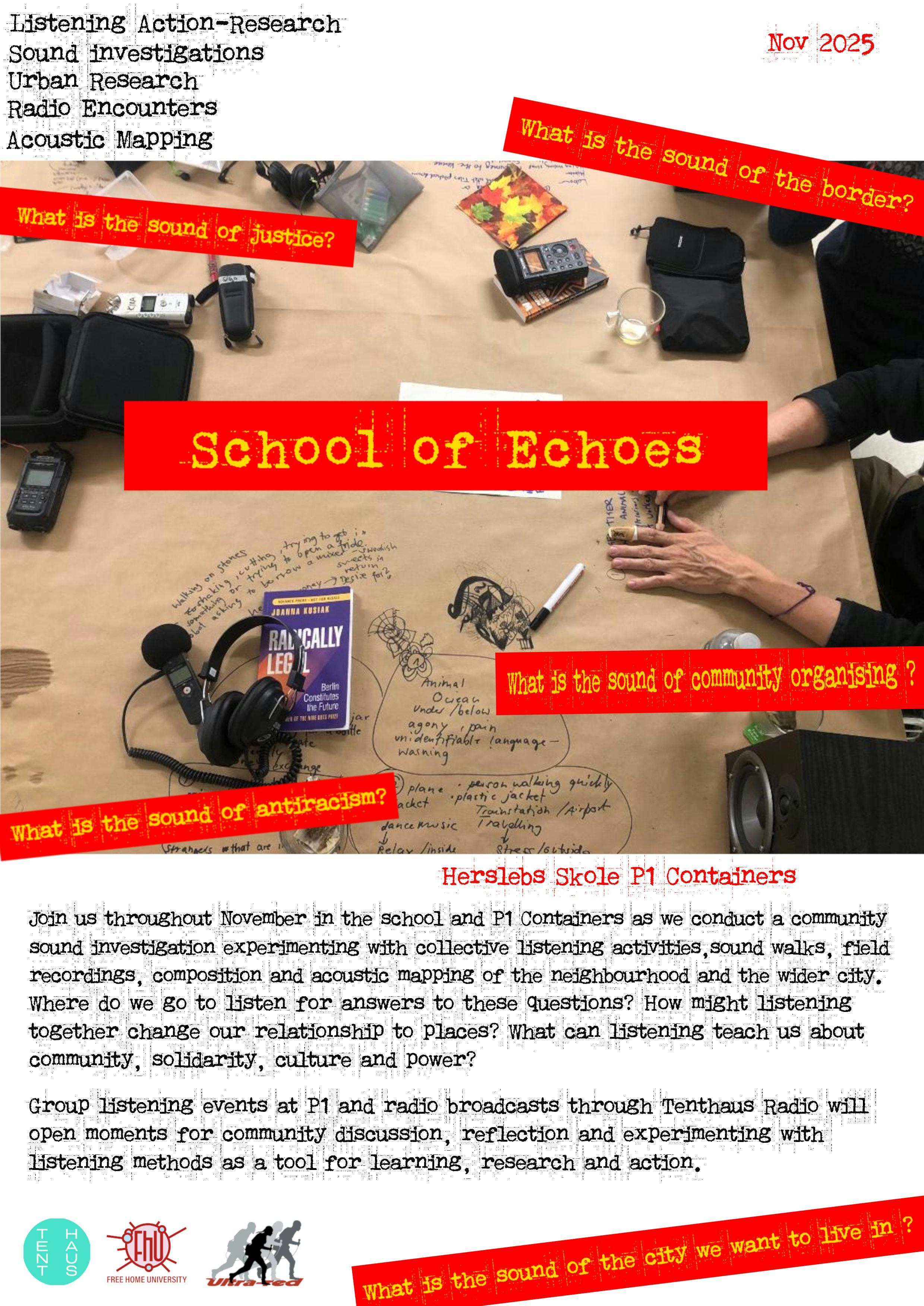

Cinema is always a matter of encounters. For us this can happen with places, people, literary texts, music, lichens, birds, ghosts, forgotten archives, other filmmakers …

In Otranto, with our comrades from the Ecoversities Alliance, the encounters were multiple. During our own gathering in Lecce, we came to see Gente di Farina, Sale e Acqua [People of Flour, Salt, and Water], a collective film by Chto Delat which poetically maps the encounter of different people trying to find a way of living together inspired by Zapatismo: members of Casa delle Agriculture, artists from the Russian collective, and a number of “displaced” people … though, watching the film the sensation is that we are all displaced in some way, and through care and solidarity we can construct a new sense of belonging.

I remember our arrival in Otranto, looking at the sea in that icy December twilight, the unbearably beautiful combination of blue and purple hues. I couldn’t help thinking about death; you almost feel it rising up on the waves. And the Castle, where the screening would take place, is a magnificent fortress, however contradictory that sounds.

A classic establishing shot announces the beginning of the film—a word I use with caution—of People of Flour, Salt, and Water. But here in this shot (another term would be master shot) there are no people—which, come to think of it, tends to be the way with establishing shots. People are implied but, apart from a passing car, they remain stubbornly absent, missing, as a philosopher once said. It’s almost as though there was a fundamental dissonance between the idea of establishing or mastering the sense of a place, a community, and showing the people who inhabit it. Because people—people in their gatherings and dispersions and desertions— don’t fit the frame of representation and will not be mastered by any shot. They enter and leave, traverse, stay hidden ...

Nikolay’s voice-over speaks in Russian: “Once upon a time in the blazing Summer of 2019…” it says, breezily oblivious to the contradiction between chronological time and the time of fable, or perhaps hinting that fable may be the saving grace of history. The voice continues speaking of Castiglione, the village in question, as “a town of one thousand inhabitants,” potentially leaving a place for the “and one” of renewal, the new day that is fable’s reward for cheating death, inventing an escape route from a plot—the construction of Fortress Europe—that moves deathwards. The “and one” refers to those who arrive in droves but each arriving as a singular being, whose tales of perilous journeys from afar ensure that the story will never arrive at its mortiferous conclusion.

Which brings us to the title. In what sense will these missing people who we will soon encounter be of flour, salt, and water? The first indication of the people to come is the breadboard that falls almost with a chopping motion across the scene, doubling as a clapperboard. The film can now begin but from a space and a means of production that will no longer be only cinematic and that puts home (the domestic sphere of reproduction) and the world into an intriguing new conjunction.

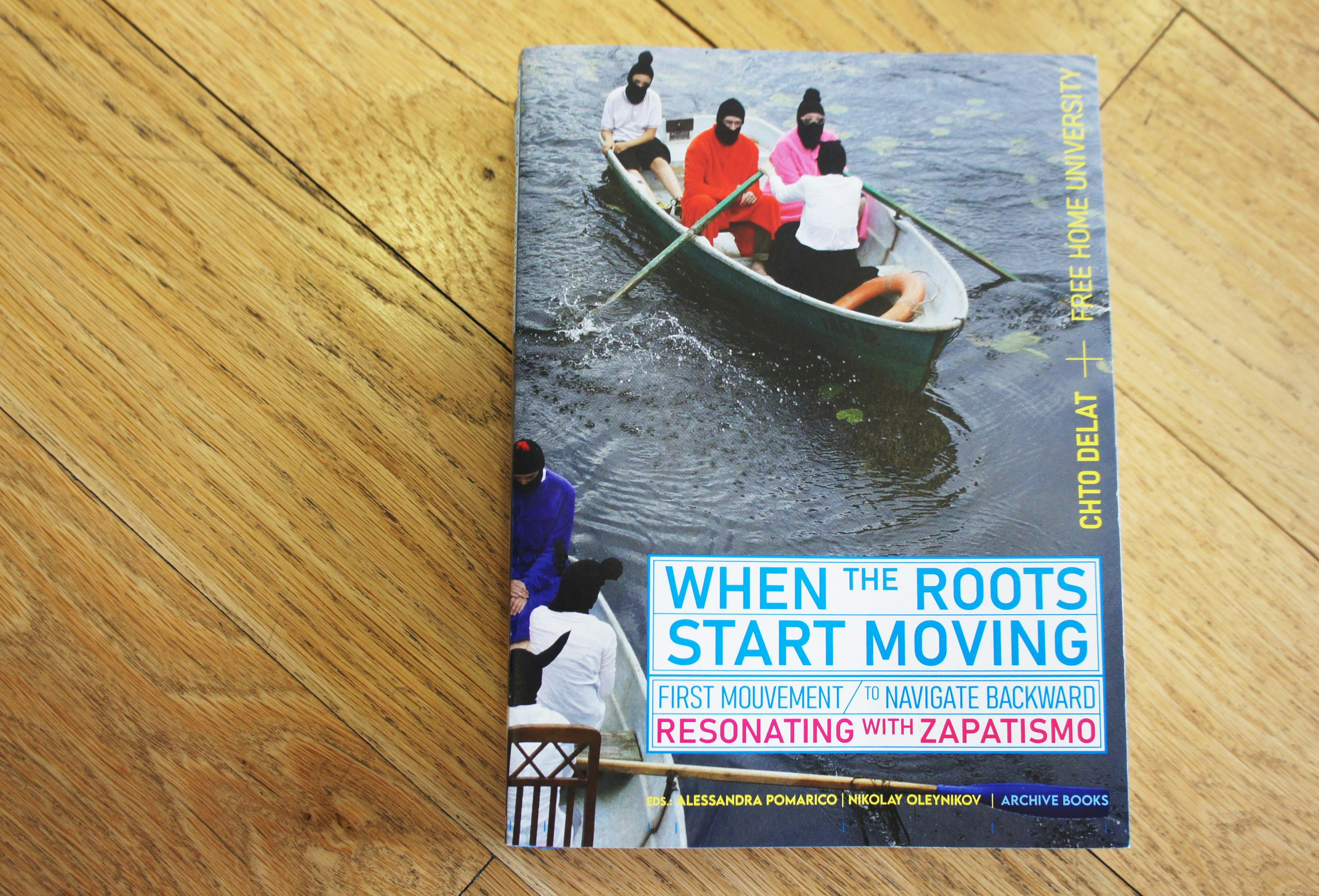

The breadboard is an image but it also announces the film’s method, a plane of non-linear composition in the form of unnumbered chapters in which something will be made or done (and we immediately understand that the film is not merely to be followed but perhaps assembled, like a kit). But it’s equally a space of preparation, where flour, salt, and water are kneaded into dough. Dough for pasta, evidently, but also for the creation and fabulation of subjectivities through the fashioning and play of avatars—a familiar Chto Delat strategy that was also deployed in their previous film on Zapatismo [2]. Only here the avatars will be made of a material characterized by its softness, malleability, elasticity, and whose eventual forms remain open and uncertain.

It’s like the group photo scene where the people are introduced, which confirms the impossibility of framing or portraying a collective subject. The freeze frames in the sequence stand in for the photographic instant and at the same time become unreliable shots from which the process of life—of the group’s readjustments and re-attunements—continually escapes.

Moreover, we are in medias res. And in this milieu there is always a possibility that someone will join, or that someone may leave. The portrait remains unsettled, fluctuating—the voices raised to sing the Zapatista hymn never coalesce into a single harmony, they wander, err through lyrics that are full of holes … A promise that alerts us to the unfinished nature of the film, “like the revolution.”

Indeed each element inhabits a suspended temporality between the already and the not-yet. Often things are visually referred to before they are mentioned, they appear in advance of their construction.

So each chapter is a kind of haiku of incompletion. It shows us a miniature of a situation, a narrative or a microevent from which we are torn at some point, often quite abruptly. We pass on to the next chapter but at the same time the tearing allows us to stay longer with the sequence we have just seen, to inhabit the resonance of each of these haikus and let it permeate what follows. In this way the structure of the film remains open; despite and because of the rhythmic cuts, we feel invited to mentally prolong gestures, songs, and stories, to build with them and give their gathered energy a lasting duration.

And this sense of the open is enhanced by the use of a hand-held camera; images that tremble, that move, are moving, allowing unforeseen movement to enter, like the dragonfly’s graceful trespass of the frame, a motif repeated at the end of the film.

Contrariwise we have a series of fixed images of the olive grove. Here, though nothing appears to be moving, it is our perception itself that shifts, as we gradually discern, half-hidden among the branches, the forms of human limbs, somehow transformed by their proximity or adhesion to the trees into natural extensions of their being, somewhere beyond either plant or human.

Then we learn from Alessandra’s voice that the olive trees in Salento are falling ill, becoming spectral figures, ghosts of the vegetal world. The bodies in the trees are perhaps involved in a reciprocal healing process, part of a poetic reimagining of ways of living together and being closer that traverses the body of the film… A film that heals and that is healed by those who inhabit it.

In this respect, the way we encounter the group’s members is particularly powerful. A split screen shows on one side a brief text while on the other we see the figure in a state of suspended repose, from which at some point they begin to sing what is perhaps a lullaby...

Are they all lullabies? More than simply conveying memories, they seem to carry childhood across the waters to rediscover itself trembling in the precarious present. And this is echoed by the sequences of the musicians and their instruments playing in the dark, the way they seem to form the image of a fragile vessel bobbing on the blackness of the surrounding night.

When we encounter Friday and Augustine, and read on the screen of their experiences of prison and torture in Libya, the splitting/redoubling of presentation into narrative and musical lines allows a river of silence to flow between, a reserve of reserve.

Because making cinema politically is always a question of presentation, allowing people the space and time to construct the fabric of what they desire to reveal, elide or invent. Too many films fall into the trap of representation, which in the case of migrant stories can be an unwitting extension of colonial violence.

Yes, and the elements from which the film’s imagined collective territory will be assembled —“a land we can call our own”—are all materially embodied. We see the sets, props, and figures as they are being created, whether it be the hanging of Zapatista slogans or the modelling of dough into avatars. Through this constructivist approach, a tentative sense of togetherness emerges out of a realignment of displacements and belongings… we feel that everything is home-made but that the home is entirely in the making.

Chto Delat describe this work as a learning-film. But who is the subject and what is the object of this learning? One has the impression that the learning process involves not only those who take part in the collective experience but questions the very concept of what constitutes research, a film, a production. While there are clear echoes of the Dziga Vertov Group and a kind of Brechtian pedagogy, at the same time the film travels far beyond their mock-stentorian classroom mode. Though ludic in its approach, it becomes a transformative experience for those involved, and for the camera, which is affectively always with the people in a process within which the viewer, too, can learn.

I keep seeing the image of Glasha’s face in the water. We know already from the chapter title that she does not drown but, seeing the tension in her face as she holds it just under the surface of the water in the bowl, following the bubbles of her fragile breathing, we feel and fear for her, although we know that she will be saved.

In fact it’s the closeness the group has attained in their co-learning that makes this gesture possible.

Because, as the film says, “just as we will drown together, so we will be saved together.”

When the Roots Start Moving || First Mouvement: To Navigate Backward || Resonating with Zapatismo

When the Roots Start Moving || First Mouvement: To Navigate Backward || Resonating with Zapatismo Travel to Salento Zapatista || notes by Christian Peverieri

Travel to Salento Zapatista || notes by Christian Peverieri Making Films Zapatistically || essay by Tsaplya Olga Egorova

Making Films Zapatistically || essay by Tsaplya Olga Egorova