Travel to Salento Zapatista || notes by Christian Peverieri

Travel to Salento Zapatista*

by Christian Peverieri

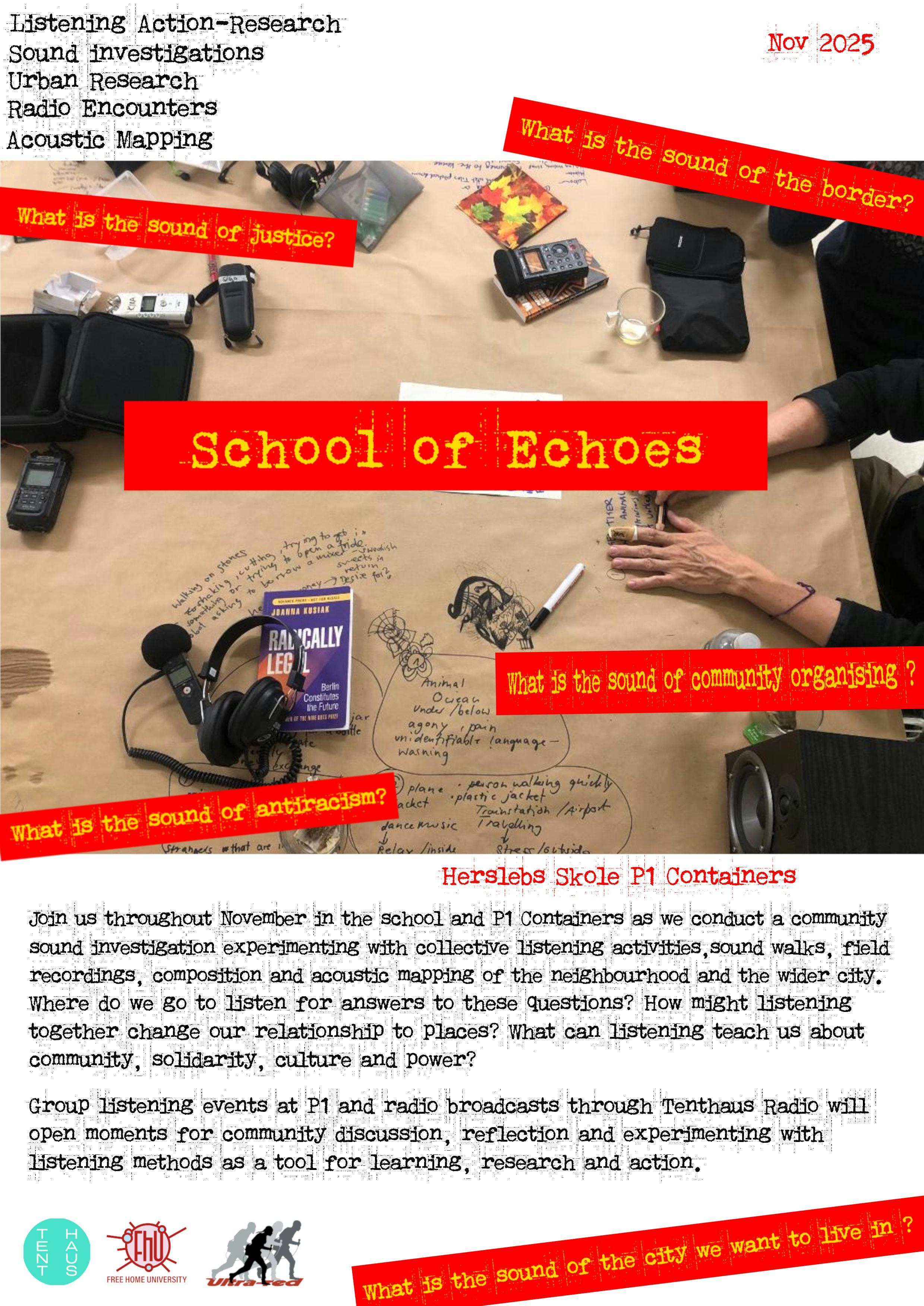

At the end of June 2019, I took part in the new social and artistic project led by Free Home University involving Chto Delat collective, together with a group of refugees, young artists, and activists.

The invitation to participate in the project—one that envisaged the production of a film and the use of several texts by Subcomandante Marcos[i] as a way of approaching group discussions—was an opportunity to pool lived experiences and our knowledge of Zapatismo, adapting them to the different social and environmental struggles shared by the participants.

Free Home University[ii] is an educational and artistic experiment created by Alessandra Pomarico with many other contributors interested in collaborative knowledge and artistic collective practices focusing on co-creation and sharing knowledge through living communally, in a non-hierarchical environment in which freedom is nurtured (Free), within a protected and close-knit space (Home), dedicated to supporting an expanding community of learners (University).

Working with a methodology reflected in Free Home University’s core values and ethos, I took part in the afternoon sessions with Augustine, Friday, Modu, Rebaz, Ebrima, Giacomo, Glasha, Asia, Donatella, and Gigi, retracing the path that led the Zapatistas to rise up against the oppression which for over 500 years had been inflicted on the Indigenous Mayan communities.

Together we discussed the Zapatista experience and their “imperfect” history, one not to be followed blindly but instead considered as a kind of work in progress, and which—amid the errors, doubts, global debates, and moments of insight— was able to build its own autonomous path. In this way, the Zapatista experience became an example of a new social model based on fostering mutual respect between men and women, and embracing the land—not as an exploitable resource, but rather as both a territory and an entity integral to one’s life.

La Favola della Scimmia Bianca [The Tale of the White Monkey] written by Wu Ming in Mexico in 2001 during the March of the People of the Colour of the Earth[iii], was one of the readings that we studied during my visit that really enabled me to get closer to the lived experiences of the participants with whom I shared time with. The fable became a lens through which we were all able to recognize our own stories and bear witness to the stories of others with empathy and in solidarity; the tale, whose main theme is the difficulty of being accepted in a new community, created a space for the stories of these young asylum seekers and their daily challenges living in Italy.

Free Home University’s emphasis on approaching texts through collective reading allowed for an emergent and enlivened transmission of knowledge: an exercise in opening multiple interpretations, reflections, translating into many languages, and formulating meanings following various contexts and mindsets. Through these methods, the sharing of personal stories and the pooling of experiences can benefit all, moving the group from an individual to a collective perception.

Another strong element of the session I attended was coming from the embeddedness of Free Home University in a local community of farmers who are very active in the defense of the commons (the soil, the land, the water, and the interrelatedness of different species). To be immersed in this context allowed for an understanding of how the local community organizes itself, attempts to live in ways that are centred on relationships and the wellbeing of the community, and not simply on financial transactions.

This particular way of creating and facilitating a learning space called to mind the festivals CompARTE[iv] and ConCiencias[v] which for the last few years have been held in the Zapatista community. According to the Zapatistas, the arts and the sciences have effectively lost their impartiality, having been manipulated and co-opted by the so-called capitalist hydra and transformed into a tool for the primary accumulation of profit, like all other living things—the Earth’s resources, animals, and human beings.

It is then our task to re-appropriate the arts and sciences as important tools for society as a whole, freeing them from the clutches of the market, making them accessible for the benefit of all.

In this sense, the collaboration between Free Home University and their comrades of the Casa delle Agriculture [House of Agricultures] created a situation in which to address these crucial issues. Adding to the conversation my experience in Chiapas, the influence of Zapatismo in the imaginary and politics of Italian grassroots and social movements, combined with the artistic approach of Chto Delat (which includes filming, somatics, music, storytelling, cooking and a lot of convivial time spent together)—resulted in an entanglement of experiences and ways of knowing from the bottom up, without any obtrusive teachers or looming impositions from the formal education power structures.

Why Free Home University chose this small place called Castiglione d’Otranto, at the very heel of the boot, as its encampment, became clear to me after I better understood the work of Casa delle Agriculture, the local organization passionately raising awareness around food sovereignty and the reproduction of life, land, and workers’ rights, and the wrongs of the agri-business locally and globally.

Free Home University has been working here since 2014, bringing mixed groups to live, search, and work side by side and in support of the local farmers/activists, conducting explorations together, learning from each other, activating multiple perspectives, and also recently involving in this ongoing conversation refugees and asylum seekers. Displacement is also the result of land grabbing and ecological disasters, and of the global dismantling of traditional economies, and here it often means exploitation of migrant workers in the fields.

One afternoon I met Gigi, the agronomist of Casa delle Agriculture, who explained more about the communitarian, self-organized, and autonomous structure of this rural community that, in many respects, recalls the experience of the Indigenous Zapatista of Chiapas. Gigi accompanied me to one of the spaces regenerated by the group, the biodiversity nursery, and there in the middle of an orchard, he told me the story of how it had all begun. Eight years before, a decision was made with seven local inhabitants to join forces against the phenomena of emigration from the village and the abandonment of the land. In these small Southern villages, migration to the North and to urban areas has reached alarming levels.

Castiglione itself is a village “in danger of extinction” with its one thousand inhabitants and less than 10 births a year. Without children, the schools have closed, and social services are no longer available. Migration and depopulation exacerbate the phenomenon of land neglect, already undermined by intensive agricultural methods and monocultures such as tobacco and olive crops, leading to the loss of certain traditional varieties of seeds and of natural and organic farming knowledge, and to the depletion of soil biodiversity due to the poisoning of the soil by the massive use of herbicides and pesticides.

Gigi and his friends from the Casa delle Agriculture decided to do something about this; by first obtaining the use of uncultivated lands from elderly proprietors, they began to cultivate using natural methods.

Beyond attempting to earn a livelihood through what they cultivate, Casa delle Agriculture organises cultural events with the goal of educating and involving the entire community, strengthening those relational ties that were progressively being lost in modern living. This is how the Notte Verde [Green Night] was created, a yearly festival which since 2011 occurs in late summer during harvest time, and is now a major event for all interested in natural agriculture. The festival includes four days packed with debates, meetings, workshops, lectures, and artistic and cultural events that culminate in an evening during which the whole village is transformed into a large farmers’ market and food fair, highlighting best practices and ethical production—an event in which the whole village takes part. Even the street names are changed and you are suddenly strolling on the Biodiversity Road, sitting in the Hemp Court, going to a meeting in the Stewards of Change Street, taking a turn under the Intergenerational Bridge, and so on).

In the crowded square, invaded by visitors (locals or those from further away), lectures are held on pressing themes, touching on both a local and global dimension. The focus of this year was, not surprisingly, the current ecological emergency. Artists, like those invited by Free Home University, are fully involved in these processes of community activation and community building, adding an aesthetic and philosophical level, intervening in the streets with murals (like in the Zapatista caracoles) or with banners, signs, performances, or actions, co-designing new places for the Casa delle Agriculture activities (for example, the Common Kitchen, the Animal Shelter or the Bio Toilet), expanding the conversations and the narrative produced within the community.

What is remarkable is that this organization walks the talk and puts its own slogan into practice: chi semina utopia, raccoglie realtà [those who sow utopias, will reap reality] keeping this belief alive all year long through cultural events such as the Semina Collettiva [Collective Sawing], Lo spirito del Grano [The Spirit of the Wheat] and Il Pane e le Rose [Bread and Roses]. In these events there is a continuous attempt to educate about crops and the food production cycle; at the same time, these are opportunities for healthy social interaction, in which ties and relationships are strengthened, achievements celebrated, and new challenges discussed and taken on. All this is amplified through art, culture, poetry, music, and high-quality food produced without over-exploiting the Earth or people’s labour, and shared with love and care.

It is a long-term project undertaken by Casa delle Agriculture with determination, persistence and considerable effort, while the whole community is becoming more conscious and able to recognize, defend, and appreciate the enormous wealth of its own territory.

It is important to highlight how a fundamental step for these new peasants, dreamers, and revolutionaries was the recognition of the need to work on cultural transformation, to create a paradigmatic shift, which can only occur by involving the new generations. The abandoned primary school, closed because of low numbers of children, has now become the headquarters of the Scuola delle Agriculture [School of Agricultures] an educational programme involving even the very youngest, that offers annual courses in land education, nutrition, and native plant species, yet another confirmation that the semilla rebelde [rebel seed] has taken root in the region of Salento.

Among the many initiatives of the Casa delle Agriculture, an important step was the construction of a community stone mill, purchased with funds from a grassroots crowd-funding campaign. Located in a former garage donated by a supporter, right at the entrance to the village, it was restored thanks to the commitment of many peasant activist volunteers as well as a group of architects and professionals who offered to work pro bono.

The mill, inaugurated in March 2019, is now a focal point for those in the area who wish their crops to be stone-milled, and for those wanting to purchase flour produced and packaged at the mill, the culmination of the supply chain of cereals of Casa delle Agriculture. Every Saturday, the mill hosts a local farmers’ market where the community can purchase, along with flours and baked products, vegetables grown organically and locally. The produce here does not have any organic certification (which would involve burdensome procedures and high fees) because these peasant activists are not building profit-seeking companies but rather a community of people who trust those who work the land to do so ethically, respecting nature and work, in order to build a new world, as the Zapatistas would put it, in which there is a common foundation of trust, respect, and honesty. The quality of the produce is guaranteed by the people themselves; they are fully motivated to ensure that the prices of natural produce and their quality are accessible.

I learned that a point of reference and somehow a kind of a patron saint for these people is Gino Girolomoni: the Casa delle Agriculture association is also named after Gino and his wife Tullia. He is considered the father of the organic movement in Italy back in the 1970s and one of the first to set out on the path of organic farming, understanding the importance of the “back to the land” movement. This so-called new way of cultivating land, without dangerous fertilizers and pesticides but in complete harmony with the soil and the non-human species, has often been hampered by obtuse laws that viewed organic farming as illegal, to the point that Girolomoni’s produce was impounded for being “harmful” to health. Gigi explained that just after returning from a collective journey to Gino and Tullia’s native village and farm, the group from Salento decided to embark on their own path, promising each other that they would persevere in their decision.

The week in Salento concluded for my family, who participated in this adventure, with an invitation to the Ode to Saragolla, a celebration for an ancient type of wheat originally from Iran and derived from Khorasan wheat. A festivity, needless to say, which used no electricity and was organised in the wheat fields and between rows of olive trees. One arrived there by following the simple and poetic directions of Gigi: Follow the sun and the wheat.

These lines remind us of how the only sustainable future is one in which we are forced to choose radical forms of life in complete harmony with the land. How this ties in with the Zapatista experience can be seen in the words of the Uruguayan thinker and activist, Raúl Zibechi: Beyond placing limits on the projects of those de arriba [top dogs] we should construct and create life there where the system sows only death in all directions.

This travel into the Salento Zapatista proved to be an opportunity to also explain the influence that the Zapatista experience has on social movements in Italy and those struggling for “a world in which many worlds fit” as the Mayan people would say.

The arrival of the Zapatistas on the international political scene with the levantamiento of January 1st, [vi]1994 (date of the beginning of the Zapatista’s uprising) was a hurricane which engulfed a whole generation of rebels everywhere, and in Italy as well, where we were still dealing with the awkward past of the 1970s, reflecting and attempting to transform the way politics was built by those generations. When the Zapatista erupted, we witnessed an army of Indigenous people rising up in arms not to conquer the Winter Palace but to establish and defend their right to exist. For the first time in history, an army laid down their arms after only 12 days of fighting, continuing with their struggle by using the word as their only weapon.

The Zapatista revolutionized the way of making revolution, rendering concrete and tangible the warning that if you wish to change things you must first change yourself, that is, that changes in one’s personal life need to be met by changes at the collective level. For the movements of the North East of Italy in which I participate, the arrival of Zapatismo coincided with the period when the federalist, conservative and secessionist phenomenon of the so called Lega Nord [Northern League] prevailed in our region, proliferating as a political discourse and taking root in the social mindset. The independence actively promoted by the League, proposing the idea of separating the rich and productive Italian North from the presumably underdeveloped, corrupt and lazy Centern and Southern regions, also spoke of exploitation of the territory, of substituting national or international finqueros [landowners] with local ones, and of a top-down decisional model. This approach has nothing to do with the autonomy practiced by Zapatistas who instead spoke of respect for the territory, and of land rights, social justice, and the self-organisation of communities.

In my experience, the peak of this unique interplay of experiences and struggles, its correspondence to and resonance with the Zapatista vision, occurred with the dramatic 2001 G8 in Genoa, exactly 20 years ago, when it became clear how the social movements were beginning to use a dialectic and mode of struggle influenced by the Zapatista experience: the Tute Bianche [White Overalls][vii] in the movement were the counterparts of the balaclavas used by the Indigenous activists, covering their faces to attract attention, paradoxically hiding themselves to finally become visible. The declaration of war against the most powerful individuals of the Globe, which was set out on that occasion, used an allegorical language clearly evoking the communiqués of Subcomandante Marcos: On every corner of this planet, your armies intervene with weapons against the ideas and the dreams of a different world, a world that contains many worlds. (...) We will be in Genoa, and our army of dreamers, of poor people and children, of Indios of the world, of women and men, gays and lesbians, artists and workers, young and old, whites, blacks, yellows, and reds will disobey your commands. We are an army born to disband, but only after we have defeated you. (from the outskirts of the empire White Overalls for Humanity against Neoliberalism. May 26, 2001 || Genoa, Italy, Planet Earth)

Over time the link between the Italian social movements and the extraordinary revolutionary experience of the Zapatistas who, for almost 30 years, have been resisting power—has arguably grown weaker but it has not been completely lost. The rage against injustice, the struggle against the many-headed hydra of capitalism, our common enemy, is that which unites us, los de abajo [those from below].

And even if in Castiglione people are not openly referring to Zapatista politics, language or poetics, I can see a strong resonance in their practice, in the way in which their tactics and strategies are built, and how people are nurturing life, wrenching it from a system producing death, passionately and patiently weaving those essential bonds to produce radical changes, those that can only arrive desde abajo y a la izquierda [from below and from the left].

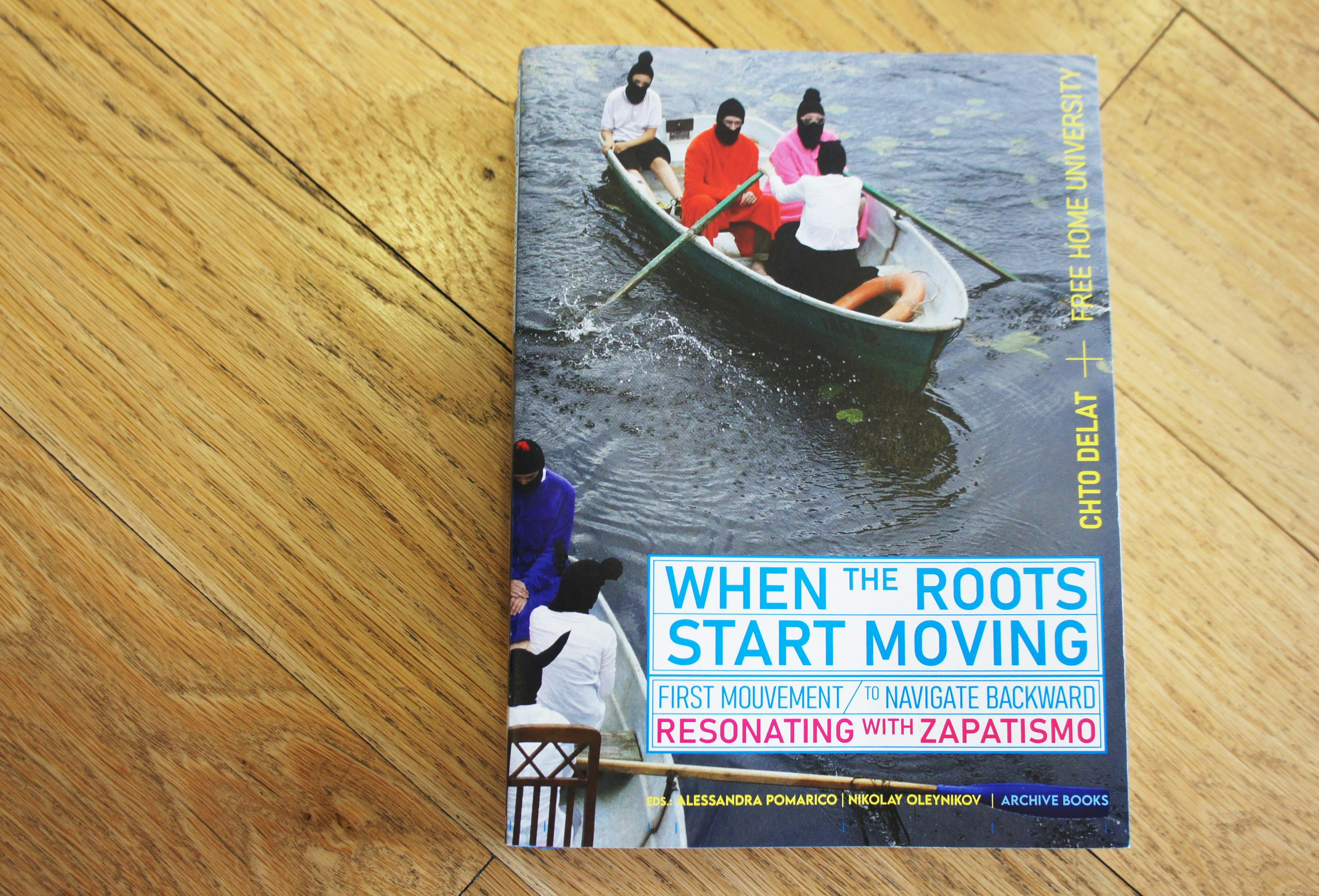

When the Roots Start Moving || First Mouvement: To Navigate Backward || Resonating with Zapatismo

When the Roots Start Moving || First Mouvement: To Navigate Backward || Resonating with Zapatismo The Fate of an Insect... || essay by Silvia Maglioni & Graeme Thomson

The Fate of an Insect... || essay by Silvia Maglioni & Graeme Thomson Making Films Zapatistically || essay by Tsaplya Olga Egorova

Making Films Zapatistically || essay by Tsaplya Olga Egorova